In Dallas for the American Library Association conference, I took the opportunity to walk through Dealey Plaza and have a look at the Book Depository. I happened to be there early on a Sunday morning and the area was all but empty. Perhaps it might have seemed different with crowds of people moving through it or cars passing back and forth, but I was struck by how close everything was. Standing on the corner that President Kennedy's car was heading toward when the shots were fired, I could see right into the sixth floor window, and the grassy knoll was less than a baseball toss away.

Standing there, it felt impossible that a person could have missed the sight of a rifle muzzle coming out of the window or a puff of gunsmoke over the knoll or have not been able to differentiate the sound of gunshots coming from two separate locations. Of course, I was not there. There were no people around me. My eyes were not locked on a presidential motorcade. But I was left with the distinct impression that if a person thought there was someone else behind the grassy knoll, it would have been impossible to be mistaken about it.

I'm not going to go so far as to say it was haunted, but standing there alone, I would be lying if I didn't say how heavily the history seemed to rest in that place.

Thursday, January 26, 2012

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Dystopia Death Match

Having plunged into dystopian waters with a book, a sequel and a short story (thus far), I felt like it was incumbent upon me to look back at the august history of the subgenre. I don't think you could debate that the two books that defined it and are still its two primary exemplars are 1984 by George Orwell and Brave New World by Aldous Huxley. I'll admit a preference for Mr. Orwell's work as I lean toward darker narratives and it's black as they come. Mr. Huxley's novel is no less significant but is very much a social satire, and not quite as much a stark nightmare. In terms of literary notoriety it seems as though the scales may tip ever so slightly in favor of 1984; it is Mr. Orwell who has an adjective that actually means dystopian named for him, after all. However, they both clearly laid the groundwork for what every dystopian writer (which sometimes feels like every writer) is doing today.

A more salient analysis of what lies at the heart of each of these works -- and what specifically terrified each of these authors -- could not be found than the following statement by one of Media Ecology's pioneers Neil Postman. To whit:

-- What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny 'failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distractions.' In 1984, Huxley added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us. --

Mr. Postman clearly came down on the side of Huxley. Essentially, that's what Media Ecology is all about. Looking at the world that Orwell and Huxley saw as the future (in other words, right now), which way did we end up going?

A more salient analysis of what lies at the heart of each of these works -- and what specifically terrified each of these authors -- could not be found than the following statement by one of Media Ecology's pioneers Neil Postman. To whit:

-- What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny 'failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distractions.' In 1984, Huxley added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us. --

Mr. Postman clearly came down on the side of Huxley. Essentially, that's what Media Ecology is all about. Looking at the world that Orwell and Huxley saw as the future (in other words, right now), which way did we end up going?

Labels:

Books,

Brave New Love,

Those That Wake,

What We Become

Thursday, January 12, 2012

Lobster of Darkness

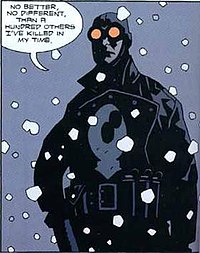

Back in the 1930s, the mysterious vigilante Lobster Johnson was the scourge of the underworld, blasting crime with his flying fists, his blazing .45 and his burning lobster's claw. His obsessive mission did not stop with crime, however. He was also the world's safeguard against the predations of evil super-scientists and incursions by the forces of the supernatural.

Never heard of this great pulp character? Probably because he was created in 1999 by Mike Mignola as a backup feature in his Hellboy comic. Since then, the Lobster has popped up in a few more short features, as a supporting character, in a miniseries and even in his own novel. An homage to actual pulp characters like the Shadow, the Spider and the Avenger, with their merciless methods and dark natures, the Lobster's past is shrouded in mystery and his adventures (originally depicted by Mignola but later taken over by other artists) were drenched in a rough-hewn shadow that made the comic pages seem to bleed an inky darkness.

If you missed his previous adventures, or even if you caught them, the Lobster begins a new miniseries this week, Lobster Johnson: The Burning Hand (by Mignola, Arcudi and Zonjic). With all the comics and graphic novels I read -- between my personal reading, my research, my committee work, my reviewing and the class I teach -- it takes a lot to get me genuinely excited about something new coming out. But Lobster Johnson is always something special. Have a look . . . if you can take the darkness.

Never heard of this great pulp character? Probably because he was created in 1999 by Mike Mignola as a backup feature in his Hellboy comic. Since then, the Lobster has popped up in a few more short features, as a supporting character, in a miniseries and even in his own novel. An homage to actual pulp characters like the Shadow, the Spider and the Avenger, with their merciless methods and dark natures, the Lobster's past is shrouded in mystery and his adventures (originally depicted by Mignola but later taken over by other artists) were drenched in a rough-hewn shadow that made the comic pages seem to bleed an inky darkness.

If you missed his previous adventures, or even if you caught them, the Lobster begins a new miniseries this week, Lobster Johnson: The Burning Hand (by Mignola, Arcudi and Zonjic). With all the comics and graphic novels I read -- between my personal reading, my research, my committee work, my reviewing and the class I teach -- it takes a lot to get me genuinely excited about something new coming out. But Lobster Johnson is always something special. Have a look . . . if you can take the darkness.

Thursday, January 5, 2012

Brave New Short Story

I recently contributed my first short story to an anthology called Brave New Love, the theme of which is dystopian romance. My story is called 357 and is about the most dystopian romance I could come up with. I am, of course, very proud to have been invited to contribute at all, but I am all the more grateful for two reasons:

1. The collection is edited by Paula Guran, who has a great sensibility for dark fantasy and whose collection The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror 2011 was recently released. I posted about last year's excellent collection here.

2. My story in Brave New Love immediately precedes Eric and Pan, a contribution by William Sleator, who -- among many other books -- wrote the great House of Stairs, a book that was hugely influential in my reading (and writing) life. It was a story that has haunted me (in the best way possible) since I read it back in my preteen days and I would have to say that it is the story most responsible for shaping my outlook as a storyteller and my desire to ask deeper questions within a dark narrative framework.

Brave New Love is available imminently in the U.K. and will be released in the U.S. on February 14th.

1. The collection is edited by Paula Guran, who has a great sensibility for dark fantasy and whose collection The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror 2011 was recently released. I posted about last year's excellent collection here.

2. My story in Brave New Love immediately precedes Eric and Pan, a contribution by William Sleator, who -- among many other books -- wrote the great House of Stairs, a book that was hugely influential in my reading (and writing) life. It was a story that has haunted me (in the best way possible) since I read it back in my preteen days and I would have to say that it is the story most responsible for shaping my outlook as a storyteller and my desire to ask deeper questions within a dark narrative framework.

Brave New Love is available imminently in the U.K. and will be released in the U.S. on February 14th.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)